Common good

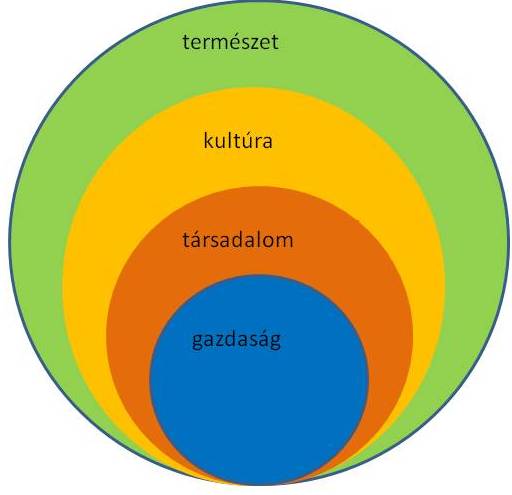

If we define the common good as the integrated, long-term sustainability of the economy, society, culture, and environment, then it is worthwhile to group together the most important issues of these areas—knowing that, individually, none of these pose any surprises to the average newspaper reader.

If we define the common good as the integrated, long-term sustainability of the economy, society, culture, and environment, then it is worthwhile to group together the most important issues of these areas—knowing that, individually, none of these pose any surprises to the average newspaper reader.

1. Economy

Due to CO₂ emissions and the finite nature of resources and inputs, the functioning of our system is already problematic today—and it will only become more so in the foreseeable future if GDP increases by even a few percent annually. Either we find solutions ourselves, or collapse will befall us. Therefore, the solution may lie in “degrowth,” which in the most developed regions means an actual reduction in consumption, while in other areas it signifies a dematerialized economy (a circular economy, the application of material- and energy-efficient technologies, etc.).

According to the OECD study Investing in Climate Investing in Growth (2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273528-en), capital can also find its opportunities—but in many areas, capital and the interests of capitalists must be constrained. An economy is sustainable only if its components are sustainable too—that is, expenses must not exceed outputs. In a simplified scheme, production can be expressed as:

C + V + M = P,

where C represents the invested capital, V stands for labor costs (which can also be interpreted as personal consumption), and M is the profit, the portion available for accumulation. However, these factors are most influenced by two elements: first, we—the people who purchase the products or avail of the services—and second, the politics we empower, which establish and operate the regulatory system.

Aggregate ecological footprint calculations are well known—but it is imperative to reach a point as soon as possible where every product includes the so-called externalities, which must cover not only current but also future expenses. (Of course, we must not forgo educating about a “well-being over mere welfare” mindset, though in terms of its time dimension—and given that such a development is largely achievable only after a certain level of material wealth has been attained, particularly in the so-called developed North, as indicated by HDI and WHR—more direct changes are needed.)

Whereas in the past production, then sales, and later marketing were the defining forces, today the economy is driven not necessarily by the satisfaction of needs but by the stimulation of desires. Modern advertisements encourage overconsumption—eliminating them, according to some estimates, could reduce consumption by as much as 30%. (With our current way of thinking, this would be a tragedy—think of the fashion and luxury industries, tourism and hospitality, the entertainment sector, including professional sports, etc.)

A money- and creditless economy is unthinkable—after all, even global climate and environmental projects require resources. Yet it has become an epidemic that it is easier to make money from money than to generate activities that serve the common good. Therefore, it is necessary to “cool down” the so-called hot money (for example, with a Tobin tax) or to enforce strategic, long-term considerations. ESG and CSR cannot be short-term (“greenwashing”) marketing tools—they must be genuine, controlled, and credible systems of principles.

While the global North is characterized by overconsumption, underconsumption prevails in the South. Tasks such as protecting arable land, reversing desertification, and preserving biodiversity, which align with global environmental protection, assume the presence of local education and healthcare—that is, they also help prevent overpopulation and migration.

Returning to the production formula: the proportion of C (mechanization, robotics, AI, intellectual capital) is increasing while the cost of labor is decreasing. The drastic transformation of the labor market is primarily a social issue—here it must be considered that, on a societal level, the amount available for consumption cannot decrease, or the economy will become unsustainable. The existing capital stock cannot be entirely reallocated to ensure sustainability (in terms of ESG and CSR), hence new projects are necessary. Accumulation of wealth is not a sin—provided it takes place under proper requirements and conditions; taxation is primarily a social issue. In a sustainable economy, fair access to resources is ensured, and operations are not jeopardized by monopolies and rent-seeking.

How well are we prepared—with insurance and recovery funds—to mitigate the financial consequences of increasingly frequent natural disasters?

2. Society

Society is sustainable if the forces of diversity do not tear apart its cohesion. Cohesion is ensured by the morals, value systems, and behavioral norms prevailing in society—the written and unwritten rules that reflect them—where mutual solidarity and trust exist and individual as well as collective freedoms and opportunities are guaranteed. This cannot mean absolute homogeneity—only dictatorships strive for that. Its main manifestations include the constitution, legitimate governance, social solidarity (fair taxation, social benefits), healthcare and education, and the application of deliberative mechanisms in decision-making.

Diversity guarantees plurality, variability, the existence of small communities and local economies, creativity, and constant renewal. The separation of powers, pluralism, and the implementation of subsidiarity all serve diversity—but their accepted frameworks and limits ensure cohesion. The social and political organization of different countries varies greatly—and it is precisely the current interpretation of the common good that could bridge these differences.

Significant cultural differences exist between countries—which in turn affect the functioning of institutional systems. For example, in the Scandinavian model, social participation is significant—in exchange, high taxes are accepted—whereas in Latin countries, individual paths are chosen and taxation is avoided. It is not merely a moral issue that the wealthy should assume greater responsibility—the proper social transfers, ensuring purchasing power, or even long-term sustainability are also in their own interest.

The purpose of taxation is twofold: firstly, to collect the resources necessary for social expenditures (public administration, social insurance, pensions, social benefits, public transportation)—which can pertain to local, national, or regional objectives, to finance sustainability projects (both locally and globally), for defense spending, and, as mentioned earlier, for compensating external effects. The sustainability of these areas must be ensured individually—for example, what can be covered by insurance and what on a benefits basis. In current systems, it is the wealthy who most easily manage to evade taxation—via financial and investment incentives, corporate real estate and asset usage, etc. Equal opportunity is indispensable for social cohesion—and inherited wealth passed down through generations leads to a patrimonial society. It is fair that parents help their children with education (e.g., obtaining a diploma) and kick-starting their careers (housing, a car). However, any inheritance beyond that is considered income or a wealth benefit. Legal and political equality does not mean that there must be complete material equality, but from a grassroots perspective it is unacceptable if our fellow human beings, through no fault of their own, are starving or suffering—thus, ensuring a minimum standard of living is a fundamental goal. Beyond that, surpassing the so-called social minimum is necessary so that one is expected to care not only for one’s own daily survival (after all, a vote cannot be bought with a kilo of dried pasta) but also to consider whether to spend all one’s money or invest in one’s future. Many claim that a universal basic income is the solution—but it remains debatable what would finance it and what conflicts might arise given the differing levels of economic development among countries. The economic section already mentioned that the role of traditional work is decreasing—raising the question of whether highly qualified jobs (e.g., those involving AI) and human-centered roles (education, social benefits, services) can be adequately maintained. Others point out that thanks to technological progress, fewer working hours will be needed. What can be done with the time thus freed? Is there any guarantee that people will devote it to creative activities, sports, or community programs? For the boomer generation, commuting to a workplace was part of their identity—it was important to physically go to work and perform tasks that sustained their families. For today’s “northern” youth, this is becoming increasingly unappealing—they are not merely slaves to consumption, whereas in the South daily survival concerns persist.

3. Culture

Our culture is what defines us: who we are, what we think about the world, and how we act—in other words, our (usually multiple) identity, which forms the basis of our humanity. Is it important for our culture to be sustainable? Everyone would agree, for our language and the basis of our social interactions set us apart from the animal kingdom; culture ensures that we can convey our thoughts, feelings, and values, learn from our past and present, and pass on our knowledge and experiences to our children and grandchildren. Through culture and art, we come to know the world best and discern what is right and what is wrong. Ideally, the education we receive from our family, schooling, and society should not be contradictory—as this determines how well we can prepare for the future.

Our identity is one of our most vulnerable assets—without it, we are rootless, yet it also distinguishes us from others, making it a dangerous tool in the hands of politicians and power-seekers. Meanwhile, as our world becomes increasingly globalized, our sense of attachment does not necessarily develop correspondingly. Our basic needs (physiological, security, social) arise from our human nature—but our self-esteem and self-actualization are nourished by our family, school, and society itself. In Eastern cultures, loyalty to the individual, family, and the ruling or higher authority remains; in the Middle East and Africa, tribal mentalities still prevail, often leading to bloody conflicts. Western culture, born of the Enlightenment, introduced the demand for individual rights—while nationalism became the basis for state organization. Within national or state frameworks, the role of the individual has grown increasingly important—but with the disappearance of the traditional family model, the role of local communities has diminished, leaving many feeling vulnerable in the face of 21st‑century changes—thus, for many, populist nationalism provides identity and an appearance of security. A not thoroughly researched hypothesis even suggests that the countries topping happiness indexes (HDI, WHR) are those where multiple identities (family, residence, workplace, interest groups) are characteristic—while the seemingly unlimited possibilities of the virtual realm do not provide a true community. The previously strengthening liberal democracy has receded—not only in Africa but even in its homeland. (While liberals were often excessively preoccupied with civil rights—for instance, “woke” or “cancel” culture—populists have seized control of the demos.) Social media, with its immediacy and accessibility, hinders genuine discussion, equating the opinion of a subject-matter professor with that of a troll. Deliberative mechanisms are rare—they require considerably more time and resources compared to daily debates. The element of time is also crucial in defending against trolls and fake news: unverified human and machine bots disseminate unchecked data and news without fact-checking.

For a community defined by a given identity, other cultures and communities may pose a threat or evoke a sense of insecurity. New York, London, and formerly Lebanon serve as examples that a “multicultural” lifestyle can be viable—as migrants were welcomed for their labor. The 2015 European migration wave highlighted this duality: while liberals neglected the real challenges of integration and assimilation, national radicals, exaggerating these issues, exploited them to instill fear, presenting themselves as the solution. There was neither time nor space for discussion—discussion that might have led to regulating migration at its source: if people can thrive locally (with jobs, schools, healthcare), then far fewer will set off. If there is a legal pathway for employment, illegal options are less likely to be chosen.

The preservation of cultures is facilitated by subsidiarity or the “think global, act local” approach. Our primary living environment is local—but if we consider that every activity, service, or decision has its appropriate level, then we must also accept the necessary existence of regional and global levels.

4. The Environment

In fact, it is not “nature” itself that must be preserved, since as long as even one bacterium lives on Earth, living nature exists—it is the nature of which we are a part, which fundamentally ensures the well-being and prosperity of our species and society. This means that we must restore to nature everything we have taken from it, that which it cannot regenerate on its own.

It is impossible to briefly summarize the most important issues of nature conservation—we understand what it means that temperatures are rising due to the greenhouse effect, and that we can realistically influence only the amount of CO₂. Forecasts suggest that the Gulf Stream may cease, permafrost may thaw, releasing additional substances (e.g., methane) into the atmosphere. Weather will become warmer and more extreme, and due to the melting of polar ice, sea levels will rise—the challenge of energy storage remains unsolved, reserves of materials indispensable for high-tech are finite, the quality of arable lands is deteriorating, biodiversity is decreasing, desertification is continuously increasing, and even irrigation water supplies are dwindling—as previous sections have demonstrated the impact of all these factors.

Key issues: Forecasting future events inevitably contains uncertainties—uncertainties that can be exploited by skeptics and/or those whose current positions might be threatened by taking measures. Many see business opportunities in the melting of the ice cap. The steps to be taken for the sake of the future inevitably come at a cost.

There is significant uncertainty as to whether climate goals can still be reached or whether changes can be moderated. Many argue that only so-called deep adaptation can help—preparing for individual and small-community survival. (Consider what would happen if the power supply were interrupted, even briefly. It is important that local communities are prepared; that self-help networks, emergency plans, and increased local awareness are in place, as social cohesion and community organization significantly contribute to managing risks.)

We talk more than we act in order to implement local, self-sufficient organic farming and an environmentally conscious lifestyle—but we do not know for how many of the eight billion people this is a realistic possibility. How prepared, how smart are our cities to be ready for the changes? From many small ideas—for example, painting cars and rooftops white to reduce heat—what magnitude of change can we expect?

Epilogue:

Is there a solution? We often observe that experts in each field can argue their positions with scientific thoroughness in defense of their viewpoints. In the rare cases where they manage to convince others, such debates are primarily aimed at the public—as in electoral campaigns, where the goal is not consensus but winning voter sympathy.

For parties with originally opposing or differing views to reach any agreement, they must find a common platform on which they concur—a platform that is typically far removed from their original positions and objectives; one might say they must ascend to another dimension. In these overarching discussions, I have found that instead of relying on the previously established philosophical, political, economic, and religious approaches to the common good, it is more practical to adopt a definition based on the integrated, long-term sustainability of the economy, society, culture, and environment.

In practice, this could be achieved if experts from the respective areas developed their consensus in an open, preferably public series of discussions (for example, initially meeting in a showdown-like manner). You may have noticed that politics has not been mentioned so far; this is because the established consensus must then be used to exert pressure on those we elect.

As time goes by and we observe that ever more money is spent on armaments—while those same funds could solve our problems—we are increasingly approaching a state in which only deep adaptation remains possible. Yet there remain optimists: Kim Stanley Robinson’s science-fiction work The Ministry for the Future is worth reading. On one hand, it is a dystopia—because the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement were not met. A series of catastrophes, both social and individual, devastate humanity: the population of a major Indian city dies from extreme heat, Los Angeles is washed away by floods from the surrounding mountains, sea levels begin to rise rapidly due to melting polar ice, power outages become continuous, food supplies falter, and hundreds of millions set off in search of a better life—as this collapse is described not only in science fiction but also by scientists. In this chaotic, apocalyptic scenario, people rise up and demand solutions from their governments. As is customary, the countries that signed the climate agreement form a “committee” in the present for the protection of future generations and all living beings—and, to our surprise, it begins to work, and the new organization is even dubbed the Ministry for the Future. From that point on, the course of events appears to turn toward a utopia (or so it seems). A measure of eco-terrorism also contributes to the realization that change is necessary—as evidenced by the emergence of so-called carbon money. (This can be facilitated by leaving fossil fuels in the ground or by reducing their use.) All forms of wealth and financial flows become transparent, and serious geo-engineering projects are implemented to slow glacier retreat and to create (or restore) natural areas.